From an Interview from the New Orleans and Jazz and Heritage Festival with John Swenson

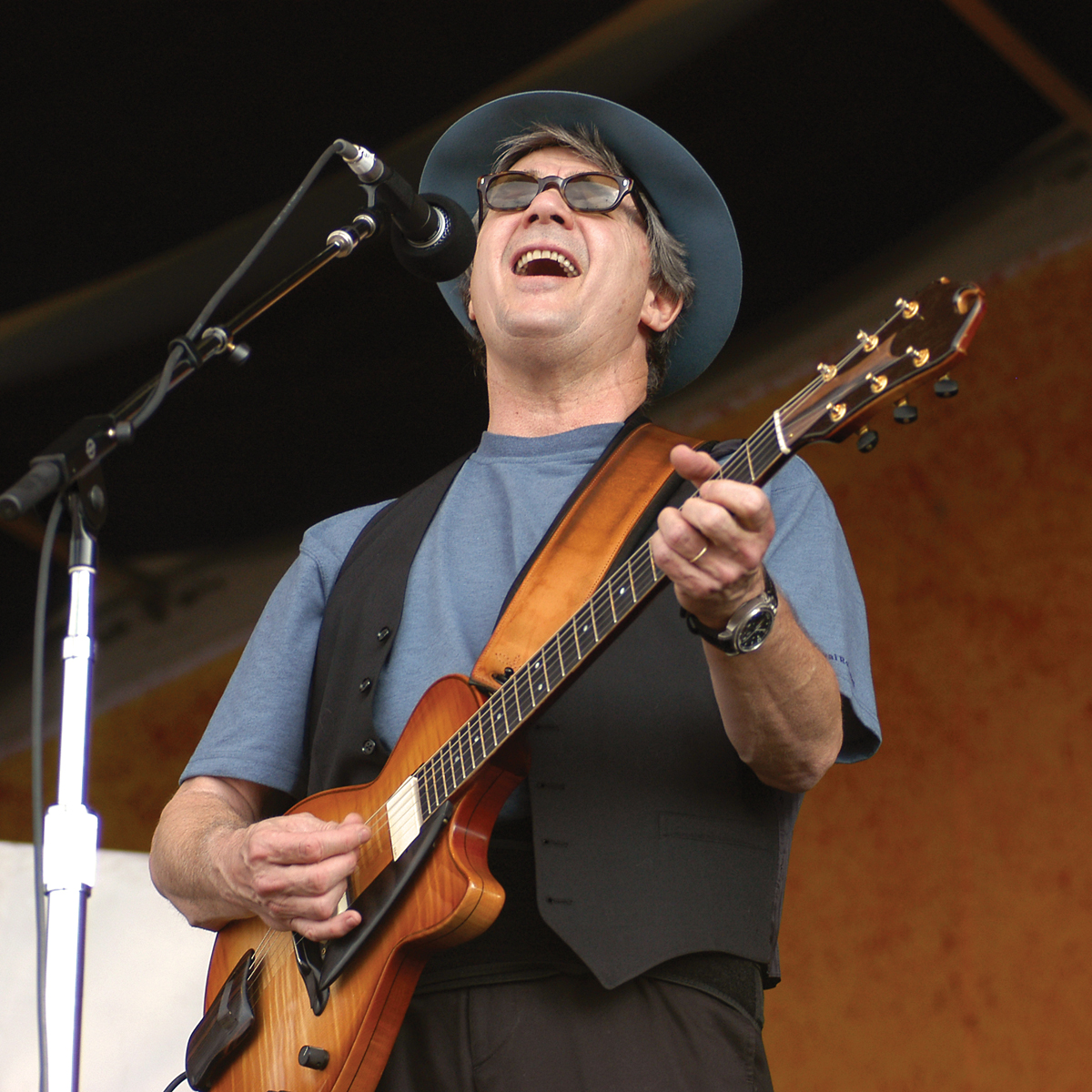

Steve Miller Band: Sunday, May 6 – Gentilly Stage, 5:20 P.M.

You might think you know Steve Miller from the hits—“Fly Like an Eagle,” “Abracadabra,” “The Joker,” “Take the Money and Run,” etc.—but there’s a lot more to this singer-songwriter and guitarist than a string of chart toppers. Even at the height of his popularity, Miller has always been a dedicated blues musician, and the lessons he learned from Les Paul, T-Bone Walker and Buddy Guy have informed his music throughout a 50-year recording career. Miller was born into a musical family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His parents were close friends with Les Paul and Mary Ford and frequently had jazz musicians over to their house to visit. Paul gave Miller his first guitar lessons. The family moved to Dallas when Miller was still a child. In Texas Miller learned about the blues and came under the wing of another family friend, T-Bone Walker, who taught him advanced guitar techniques. Miller was developed beyond his years when he went to attend college in Madison, Wisconsin. Before he could finish his studies he decided to move to Chicago and become a working musician. From there he moved to San Francisco where the opportunities for gigs were greater in the flourishing late-1960s music scene.

You might think you know Steve Miller from the hits—“Fly Like an Eagle,” “Abracadabra,” “The Joker,” “Take the Money and Run,” etc.—but there’s a lot more to this singer-songwriter and guitarist than a string of chart toppers. Even at the height of his popularity, Miller has always been a dedicated blues musician, and the lessons he learned from Les Paul, T-Bone Walker and Buddy Guy have informed his music throughout a 50-year recording career. Miller was born into a musical family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. His parents were close friends with Les Paul and Mary Ford and frequently had jazz musicians over to their house to visit. Paul gave Miller his first guitar lessons. The family moved to Dallas when Miller was still a child. In Texas Miller learned about the blues and came under the wing of another family friend, T-Bone Walker, who taught him advanced guitar techniques. Miller was developed beyond his years when he went to attend college in Madison, Wisconsin. Before he could finish his studies he decided to move to Chicago and become a working musician. From there he moved to San Francisco where the opportunities for gigs were greater in the flourishing late-1960s music scene.

Miller began his recording career backing Chuck Berry and went on to make several great albums in London with producer Glyn Johns. On his third album, Brave New World, Miller was joined by Paul McCartney on “My Dark Hour.” Miller went on to become one of the biggest hit makers of the 1970s using techniques he learned from Les Paul, but even at the height of his popularity Miller was always a blues player, using James Cotton as a sideman and including at least one straight-ahead blues tune on every album. When the hits stopped coming, Miller returned to his first musical love, playing blues and R&B. On his number one Blues album Bingo! (2010), he even cut a version of Jessie Hill’s New Orleans classic “Ooh Poo Pah Doo.”

I saw you the last time you played Jazz Fest in 2004. People obviously want to hear the hits but you integrate that material into a larger context.

That’s the trick. I’ve been doing it for 50 years. There are 14 songs I need to play. I want my audience to hear what they want to hear, the trick is to skillfully weave in those nine other songs.

Norton Buffalo on harmonica was really good that day.

Norton was the greatest. We lost him so quickly and there’s no way to replace that. We were together for 30 years I think. He got sick very quickly. It might have been some bad strain of cancer that he got just from playing the harmonica. It got into his lungs. He didn’t smoke. He was the healthiest guy in the world. He used to roller blade to the gigs while we’d ride in the bus from the hotel.

Guitarist Roy Rogers was a special guest on that gig.

The three of us together have a lot of history. I’m in touch with Roy all the time and I try to play with him as much as possible. We’re excited about closing out the festival and we’re ready to go.

This year’s festival is dedicated to Fats Domino.

I’ve loved Fats Domino from the time I was about 10 years old. I never met Fats but he was one of the first rock and rollers I ever heard. I grew up in Dallas. The closest I got to Fats was Gerald Johnson who knew Fats and his family. He was a bass player who used to play with the Sweet Inspirations. We played together for a number of years. I never met Fats but I felt like I knew him all my life because I loved his band and I loved his records.

You also knew another great who just passed away, Chuck Berry. You played with him at the Fillmore West, which was recorded and released at the time.

I played with Chuck many times. I met him in early 1967 when I came out there and rehearsed with him for a few days. This is before he got into his regular routine of just showing up and playing. He was amazing. I had a really good period of time working with Chuck—played with him 10 or 12 times. The Fillmore shows were really special because I agreed to do them but only if Chuck would come out and rehearse for a couple of days. Which he did.

You actually play a duet with him on “It Hurts Me Too.”

This year it’s the 50th anniversary of recording for me and I’m up to my neck in 50 years of photography and 50 years of music. I’m thinking about maybe putting that one on the 50th anniversary album.

It was mostly a blues record.

Yeah. We were all over him, to play blues. We rehearsed everything. ‘Rockin’ At the Fillmore,’ we did all of his stuff. The shows were a bit different. The rehearsals were the really great part of that time.

Did they record your set as well?

Nope, they just recorded us playing with Chuck. We’re just going through everything and there are not a lot of live recordings of us from the ’60s. We found a little bit of recording that Pennebaker did at the Monterey Pop Festival. They weren’t supposed to be filming us but they filmed us for about four minutes. There’s just not a lot of footage or recording of us in the early days playing live. That band was really great. I just saw that band, the one that played with Chuck Berry, last night. It was from the Monterey Pop Festival; we were playing ‘Mercury Blues’ and really kicking it out. Tim Davis and Lonnie Turner have passed away so that’s kind of sad but there we were, all about 21 years old. It was great to see.

I’ve heard that tape of you from when you were about five years old playing for Les Paul. You’re like “Hey, you wanna hear a love song?” and you’re whanging away on the guitar. You had the whole concept down already.

I had seen Les Paul play. I had been taken to the nightclub to see Les and Mary Ford. They were in town for six weeks or so and they were rehearsing their act. We went every night because we lived right in the city in this funky old townhouse, we were like a block and a half away from the gig. As soon as I saw them—it was just like every show Les Paul ever did, it was completely sold out and there were like eight guitarists on stage, a lot of jamming going on. I was just doing what I saw Les do. I knew I wanted to do this as soon as I saw Les and Mary and how much fun they were having. I was already singing and playing and my uncle had already given me a guitar. My mother and my aunts and my cousins were there so I was singing harmony rounds with them. By the time I was two I was singing harmony rounds on ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat.’ I had an uncle that played violin in the Paul Whiteman orchestra. We had lots of professional musicians coming to the house for meals. We were in Milwaukee and all the big bands who would come and play Chicago would come to Milwaukee for an extra gig. Charles Mingus used to come over and Tal Farlow, Red Norvo. I was growing up seeing people play music and of course my parents loved music so I just thought that was the greatest most natural thing to do in the world. I would pretend I was making up songs.

That tape you heard, I was on the second floor of the house, banging on the guitar my uncle had given me, all my little pals were down in the alley behind the house and I was like doing my show. My father snuck in and made a wire recording. I was so mad at him I was absolutely furious that he would sneak in and record me like that. It was the first time I’d ever heard my voice back and I was like totally freaked. What happened was that Les Paul was visiting, there were a lot of parties, drinking, smoking, a lot of music. It was right after World War II and these people were really letting loose. My dad wanted to play it for Les Paul and I was extremely embarrassed by it so Les Paul paid me a quarter to listen to it and that was like my first paying gig.

He taught me so much. He taught me my first three chords which were one finger chords, the I-IV-V. He told me when you put out a single you’ve got to send out a package of 100 post cards to every city requesting your tune as if it were from lots of fans. I knew he was speeding the tape up and slowing it down. It was 1949. I didn’t know he was a genius. I didn’t know he was kind of inventing the electric guitar. He was just my godfather and this really cool guy who was at the house all the time.

Did those studio techniques help you conceptually when you started to record?

Oh yeah. I was completely into singing harmonies, doing the multitrack vocal work and multitrack guitar parts. I’d already been ping-ponging between two quarter track stereo machines, using tape reverb. Everything Les did is what people do now when they make records. They make them at their house, they use tape echo, Les is really the guy who started all that. He was making his records in his house in the ’40s. He was the first guy who said, ‘This recording studio environment sucks.’ I never thought I was going to be making my own records until I was about 20 years old. I saw what he was doing and just absorbed it. My dad had a Magnacorder. Tape recorders were brand-new, it was a new thing—German technology. Les had the second tape recorded available in the United States. When Les and my dad met they were like two of the 20 people in the United States who had tape recorders. They loved each other. My dad would go to record them where they were rehearsing at this place called Jimmy Fazio’s Supper Club in Milwaukee. Les and Mary got married in Milwaukee and my mom and dad were the best man and the maid of honor. They spent their honeymoon in my parents’ bedroom.

As soon as I could sing harmonies with myself in the studio I was doing it. And that turned out to be how all the pop records in the ’70s were made.

When you moved to Dallas you met T-Bone Walker.

Yeah. Milwaukee was like a jazz scene. This was the end of the war. I was born in 1943. They dropped the atomic bomb in 1945. We’re talking about 1950 when we moved to Texas. When we got to Texas it was a total shock. Number one it was segregated. My parents were hipsters, they loved jazz and blues, they had black friends, which was just not acceptable back then. They accused my father of having race parties and arrested him.

There was a huge musical stew going on in Dallas. The Big D Jamboree was on, which was basically an outlier of the Grand Ole Opry. We had Louisiana Hayride from Shreveport. So Elvis would be in Dallas. I saw Carl Perkins in Dallas. They had rhythm and blues shows, they had country music, they had Mexican music, they had Tex-Mex. It was on television. There was a store in downtown Dallas called the McCord music company that was the first music company outside of California that sold Fender instruments and amplifiers. So there were Stratocasters and Telecasters and Fender Bassman amps and concert amps for sale in Dallas. You could turn on television and Freddie King was on television on Saturday afternoon on an R&B show. Or Ernest Tubb. Or Riley Crabtree. Or Hank Williams. All of this music was going on. There were black radio stations, KNOK was a black station, nothing but blues and rhythm and blues, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf. We had regular pop stations like KLIF. Then we had a DJ named Jim Lowe on WRR, a public station, PBS-style, they had a great blues show on five days a week called Kat’s Karavan. So I’m listening to Jimmy Reed, I’m 11, 12 years old, starting a band.

T-Bone Walker was a patient at the hospital where my dad practiced. He introduced himself to T-Bone and they became really good friends. T-Bone became a regular at our house, which was really unusual because it was a segregated city. He’d come over and we’d hang out. He played some gigs which my father recorded. I’ve got 21 songs T-Bone recorded at our house in 1951 and 1952. He was the sweetest man. When he showed up at the house for the first time I knew he was coming because we rented a piano and the carpet was rolled up. I stayed home from school. T-Bone showed up in a flesh-colored Cadillac convertible with real leopard skin seat covers, in a suit, just as sharp and clean and beautiful as he could be. As soon as I saw him I said you’re T-Bone Walker, show me show me show me. I sat right next to him every time he played and that’s how I learned what playing lead guitar was.

You still have that T-Bone–like style, those clearly articulated single lines.

Being around him you couldn’t help it, it was implanted in my brain. That’s how I learned how to play. Oh, this is how to play lead guitar! We just did a show at Jazz at Lincoln Center, T-Bone [Walker]: A Bridge from Blues to Jazz, and we did 20 arrangements of T-Bone songs with the Jazz at Lincoln Center horn section.

When you went out to San Francisco it was the height of the psychedelic era and your guitar sound was about the shape and quality of the notes and tones rather than how fast or loud or long, which was completely different from the whole acid rock style.

Guys like Jorma and Bob Weir and Jerry Garcia, the popular guitarists of the time, they were folk musicians who said ‘Let’s get an electric guitar and an amp and some Beatle boots and play rock ’n’ roll.’ I grew up in Texas listening to T-Bone Walker and Freddie King playing a Stratocaster through a Fender amp. When I got to San Francisco it wasn’t a musical scene, it was a social phenomenon. They were using the form as a way of drawing people to come to the psychedelic party, to take the LSD, to see the light show. It took those bands a long time to really learn to make records. They finally got it all together and started learning what it was, but when I showed up I had just been playing in Chicago for three years where Junior Wells would steal your gig if you weren’t on top of your game. Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Howlin’ Wolf… I played with Buddy Guy, I was rhythm guitar player in his band. Barry Goldberg and I put a band together and we were competing with those bands for the same gigs. Paul Butterfield was there, it was before Mike Bloomfield joined him. Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters were back in Chicago, their records weren’t selling, they were playing at Pepper’s, they were playing at the Blue Flame, they came to the North Side and were playing at Big John’s. So as absurd as it sounds, we were competing for the same gigs.

Then San Francisco opened up and Butterfield went out. I saw what he was doing and went there too. We went from working from nine o’clock at night until four in the morning six days a week in a nightclub for $125 a week in Chicago to making $500 playing to 1200 people at the Fillmore Auditorium and being treated like a rock star with a light show. So everybody left Chicago—Muddy, James Cotton, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy—everybody in Chicago pulled up stakes and went to California. That’s what filled in the scene. I played the Fillmore 120 times. I was one of the bands that was there Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, drawing people in, and the same thing for the Family Dog. We started bringing Muddy, Wolf and B.B. King out, I did the first show with B.B., I did the first show with John Lee Hooker, the first show with James Cotton. Miles Davis was there, Roland Kirk, Charles Lloyd, Johnny Cash came and played. Ray Charles came and played. Count Basie. You had the Grateful Dead and the Jefferson Airplane, those were the two sort of pop-star bands and in between you had to fill in all that space around them. The Airplane were really interesting, Jorma and Jack were really good, Marty Balin was a good singer, Grace Slick was a good singer. The Dead were like a mediocre blues band that were high on acid. Pigpen was okay, but it was like oh, boy, they’re gonna play a 45-minute version of ‘In the Midnight Hour’ that you don’t wanna hear. And then they’re gonna stand around for 20 minutes because they were high, and people loved that and thought it was the greatest thing in the world. I just came from a place where you played 45-minute sets and you had to be great instantly or they’d throw you out of the nightclub. It was a social phenomenon and in their way those bands really are great and did really great things, they created a whole new way of presenting music, with the light shows. I jumped in and joined in. They created the idea of the pop concert that you still see today with Beyoncé, just without the dancers. The idea of playing in a football stadium with a giant PA system was developed by the Grateful Dead. We all had to do that. When I started getting my audience I went from playing theaters to hockey arenas to football stadiums in nine months.

Is that why you chose to go to London to make your first album? For a different musical point of view?

I was really naive when I signed my deal. I had 14 record companies trying to sign me and I said ‘I want artistic control over everything, I want to own all my publishing, I want a half a million dollars.’ It was 1967. Capitol finally agreed to all my demands. I thought ‘Oh boy I’m going to Capitol Records, my godfather’s studio, Hoagy Carmichael, Les Paul, Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole…’ I walked in and there were a bunch of crew-cutted right-wing engineers who ran the music department. When we finally set up to record they walked out because I was a hippie. So I called up my producer and told him I’d give him the money back. But I had the right to go and record any place I wanted to according to the contract. So we went to London. We found Olympic Studios was available. Glyn Johns was available as a hired engineer.

He almost became a member of the band.

Glyn was very ambitious and he was very good at what he did and he was much more of a rock star than we were. We had to pretty much keep him off the record. Keep him from playing bass, keep him from playing rhythm guitar, from playing the tambourine. I argued with him all the time. I learned a lot from Glyn about making records. The difference between the English and the Americans was the Americans were all conservative assholes, they didn’t like loud amplifiers or big drums or any of that stuff. They were into making pop records. When you went to London they had a Marshall stack, they wanted you to turn it up, they wanted it to sound like rock ’n’ roll. They had the microphone 15 feet away from the amplifier. There was a crazy guy at the console saying ‘Let’s see if we can make it sound badder.’ It was great. We got there and Glyn was all of that. I had a lot of arguments with him about too much echo on the records. I was into Otis Redding and the Stax sound, I liked a lot of dry presence and soul. We argued about the sound of the guitars, the sound of the record. We really argued about electronics. He didn’t like any electronic sound glosses, he thought that was all bullshit. I had to really force him to do that stuff and fight for it. While I was mixing my first record, Children of the Future, Led Zeppelin was coming in, moving their gear in for their first sessions at Olympic and Jimmy Page was hanging out with Lonnie Turner and I while we were mixing Children of the Future, listening to our electronic music ideas and hearing what we were doing. It was that kind of a creative pool. Procol Harum was around, Peter Frampton was there, Johnny Hallyday was coming over, the Beatles were around, the Rolling Stones, the Who. It was much more interesting than being in Los Angeles with the Association.

So that’s how you met McCartney.

I met McCartney because Glyn was recording them. We went over to George’s house and he said why don’t you come over to the session tonight and I went over to session, they were doing ‘Get Back.’ I went back the next day and they were running over a couple of days. I was supposed to be there to mix Brave New World. We got to the studio and I think it was Easter Sunday and John and Ringo didn’t show up. We were just jamming around, then George took off and I was showing Paul some riffs and he started playing drums. We instantly became musical mates and started jamming. Glyn said ‘Let’s put it down on tape’ and we recorded ‘My Dark Hour.’ Paul did the drums and bass and he sang the background vocals and I did the guitar parts and sang the lead. Paul had a pedal steel that he let me play and we just built a record that day. That’s how we met and became friends.

You’re doing a massive reissue program this year.

Yeah, it’s our 50th anniversary. We’re putting out 18 vinyl records, a box set for September, I’m writing my biography and doing a 51-city tour. I’m working with Jazz at Lincoln Center on a series of blues programs. I’m 74 years old and I’ve got lots of energy. It’s a really creative time—I’m really enjoying myself.

On your early albums you wrote a lot of political material—“Living In the U.S.A.,” “Jackson-Kent Blues,” “Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around”…

‘Fly Like An Eagle,’ they were all political statements. When I went to college I became a student demonstrator. I was a Freedom Rider, I took a bus and went to the March on Washington. I was completely radicalized. I was very much against the war in Vietnam. I knew it was bullshit, the whole domino theory was political bullshit. There was a lot of politics in the music. As I got further along it became more important to have a positive message in my music. ‘Fly Like An Eagle’ was the last one of a series of political songs that I wrote.

One of the things about “Fly Like An Eagle,” the subtext of that song is really powerful. It really connects to a lot of people in New Orleans. The Neville Brothers covered it. The whole idea connects to Native American culture as well.

It’s interesting, we have a recorded version of it three years before it was released and there are verses in it about Indians. A lot of people don’t listen to the stuff. They hear ‘Born In the U.S.A.’ and think it’s a great tune about America. Same thing with ‘Living in the U.S.A.’ It’s amazing how so many people don’t listen to the lyrics of songs. ‘Fly Like An Eagle’ is like that and I think that’s why it’s still around and why it’s still a great piece of music for us to play live. It’s always a really important part of our live performance. I was trying to say these things as a young man when I was writing this stuff and here it is 50 years later and 200 million people have heard this or more and the songs are still around. They were always hidden in a simple shell. What they’re about was always presented in a simple way that will pull you in and hopefully make you think about what these things were really about. I’m surprised that we’re still around and have had such a great audience and I can’t wait to go to New Orleans and play. It’s such an honor to have the closing slot. The Neville Brothers used to close it. When I heard that they recorded ‘Fly Like An Eagle’ a great warm feeling just started at the top of my head and oozed down to my feet. Wow. The Neville Brothers recorded ‘Fly Like An Eagle.’ How great is that? So this is a real special gig. I guess that brings it full circle, huh?

Source: https://www.offbeat.com/articles/steve-miller-talks-back/

(Photo by Clayton Call/Redferns)